Precision Shaft Measurement

Adcole is the only company solely dedicated to enhancing the quality of cylindrical and eccentric rotating shafts used in your assemblies. Even micron-level surface deviations can significantly impact the performance and longevity of these components. Issues such as high-friction contact points and imbalances can lead to vibrations that compromise the integrity of the final assembly. Poor shaft quality can be costly—both in terms of performance and production. That’s why engineers and production managers must implement robust quality control systems and ensure they are equipped with the right tools to measure and monitor critical features with precision.

In 1957, Addison D. Cole proceeded with the founding of Adcole Corporation, now Adcole LLC, a business set to become a revolutionary industrial technology manufacturer within the automotive and space exploration industry.

Following a chance meeting in the 1960’s with a powertrain engineer from International Harvester Company, now International Motors LLC, Mr. Cole envisioned how Adcole’s calibration techniques for their fine-angle sun sensors could be applied to precision metrology systems for camshaft production. With this “eureka” moment, Adcole became the first company in the world to manufacture automated shaft metrology systems whose accuracy, precision, and durability have set a standard of excellence that has yet to be eclipsed to this day.

With Adcole’s major product lines established, it became clear to the broader industrial technology community that under the leadership of Mr. Cole, this was to be a business dedicated to solving complex problems in both space and here on earth, pushing the boundaries of precision, accuracy, and quality, and forever to be recognized as the leader in TRUSTED ACCURACY systems.

Why Adcole

With over 60 years of expertise, Adcole has set the industry standard for shaft gaging—becoming the benchmark against which all others are measured. Dimensional accuracy is critical in many shaft features, and Adcole gages are ideally suited for these high-precision applications. Typical examples include lifter lobes and bearing journals on camshafts, thrust faces and pin journals on crankshafts, and shaft diameters and gear teeth on EV rotor shafts.

Parameters Measured

Angularity

Angularity controls the orientation of a feature at a specified angle (other than 90°) relative to a datum.

Barreling / Center Deviation

Chatter

Concentricity / Eccentricity

Cylindricity

Diameter / Radius

Used to indicate that a tolerance or dimension applies to a cylindrical feature, such as a hole or a shaft. Diameter is based on a single radial measurement. The follower readings are summed up and divided by the number of data points per revolution, and then multiplied by two to get the average diameter.

Flatness

Linear Parallelism

Linear Taper

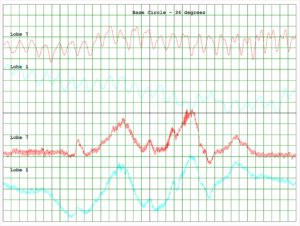

Lobing

Parallelism

Perpendicularity

Ridge Detection / Material Build-up

Roundness

Runout / Total Runout

Slope

Straightness

Taper

Throw (Rods)

This parameter is calculated using the information from the computed centers of the two outer cuts. The distance between these centers and the specified part axis determines the throw.

True Position (Rods)

Width (Mains and Rods)

Z-position (Mains and Rods)

Software

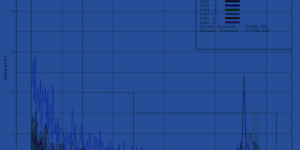

These tools often include features for tracking defects, analyzing performance metrics, and generating detailed reports. By providing insights into areas for improvement, Adcole gage software helps your organization maintain the highest standards and continuously enhance your products.